Sunday, January 31, 2010

This week in search 1/31/10

This is part of a regular series of posts on search experience updates that runs weekly. Look for the label This week in search and subscribe to the series. - Ed.

From Google Squared enhancements to search becoming more social, this week brought a slew of exciting and (we hope) useful search feature releases:

Social Search

Sometimes, there might be relevant content on the web from people in your social circle. For example, learning what your friend thinks about the latest gadget or exotic travel location (e.g. in his or her blog) can help enhance your search experience. Until recently, there was no easy way to find this type of content published by your friends. Last October, we launched Social Search in Google labs to help solve this problem.

After a large number of users opted in and tried out the feature, Social Search has graduated and is available in beta for all signed-in users on google.com in English. We also added this feature to Google Images and gave you a way to visualize your social circle. To learn more about Social Search and how to get better social search results check out this post or this video.

Google Squared single item landing page

Last year we launched Google Squared, an experimental search tool that collects facts from the web and presents them in an organized collection, similar to a spreadsheet. For categorical searches like [us presidents] or [dog breeds], Google Squared produces the type of extracted facts you might be interested in, and presents them in a meaningful way. Starting this week, Google Squared has a new design to better handle queries looking for a single thing, like a specific president or a particular breed of dog. The page is now easier to read and includes multiple images, and you can still add, remove or change the type of facts that are visible.

Example searches: [barack obama] and [boston terrier]

Better labels for Time/LIFE images

In late 2008, we worked with Time/LIFE to digitize several million archival images never been seen before, and made them available in Image Search. At that time, many images in the collection had descriptions and labels and were easy to search for. But some had less descriptive information, making them more difficult to find. Now it's possible for knowledgeable users to label images and enrich the collection. Over time, we hope the Google community will make the quality of image search better than ever before.

Example: [Cincinnati baseball]. Note the "labels" in the bottom righthand corner.

We hope you enjoy the variety of new features this week.

From Google Squared enhancements to search becoming more social, this week brought a slew of exciting and (we hope) useful search feature releases:

Social Search

Sometimes, there might be relevant content on the web from people in your social circle. For example, learning what your friend thinks about the latest gadget or exotic travel location (e.g. in his or her blog) can help enhance your search experience. Until recently, there was no easy way to find this type of content published by your friends. Last October, we launched Social Search in Google labs to help solve this problem.

After a large number of users opted in and tried out the feature, Social Search has graduated and is available in beta for all signed-in users on google.com in English. We also added this feature to Google Images and gave you a way to visualize your social circle. To learn more about Social Search and how to get better social search results check out this post or this video.

Google Squared single item landing page

Last year we launched Google Squared, an experimental search tool that collects facts from the web and presents them in an organized collection, similar to a spreadsheet. For categorical searches like [us presidents] or [dog breeds], Google Squared produces the type of extracted facts you might be interested in, and presents them in a meaningful way. Starting this week, Google Squared has a new design to better handle queries looking for a single thing, like a specific president or a particular breed of dog. The page is now easier to read and includes multiple images, and you can still add, remove or change the type of facts that are visible.

Example searches: [barack obama] and [boston terrier]

Better labels for Time/LIFE images

In late 2008, we worked with Time/LIFE to digitize several million archival images never been seen before, and made them available in Image Search. At that time, many images in the collection had descriptions and labels and were easy to search for. But some had less descriptive information, making them more difficult to find. Now it's possible for knowledgeable users to label images and enrich the collection. Over time, we hope the Google community will make the quality of image search better than ever before.

Example: [Cincinnati baseball]. Note the "labels" in the bottom righthand corner.

We hope you enjoy the variety of new features this week.

Macbeth and Time: Imagination and Memory

I mentioned previously that I was reading Colin McGinn's book Shakespeare's Philosophy. Well, I just finished his chapter on Macbeth (and another one that I'll be posting on in a couple of days) and thought some of the comments on the role of time in Macbeth were interesting.

The role of time in human life is a topic that fascinates me, so I thought I'd share some of McGinn's comments, intermixed with some of my own.

Let me begin by saying that Macbeth was my first exposure to Shakespeare. I studied the play for 3 years in second-level and so it has a certain nostalgic value for me (memory and time!). Of course, it doesn't hurt that it is a genuinely great play (indeed, it is "timeless"!).

Tragedy and Time

Human life is embedded in time: we remember the past, we plan for the future and we live in the present. We swim in an ever-rolling stream.

In my post contrasting comedies and tragedies, I noted that time plays a crucial role in a tragedy. The clock is always ticking, a foreboding soundtrack to a character's ineluctable and unfortunate end. Macbeth is perhaps the purest example of this.

Macbeth, more than any other Shakespearean character, is mesmerised and haunted by time. To be clearer: Macbeth is mesmerised by an imagined future and haunted by his memories of a blood-soaked past. Consider both of these phenomena -- imagination and memory -- in more detail.

Who Will be King Hereafter

In his discussion of Macbeth, McGinn gives a broad treatment to the topic of imagination. For instance, he provides copious commentary on the hallucinated dagger that leads Macbeth to Duncan's bedchamber. I want to consider imagination more narrowly, as a speculative conduit to the future. In other words as a psychological faculty that tempts us towards a particular vision of our future lives.

Understood in this sense, Macbeth is a play all about imagination. Indeed, the play begins with a temptation. Macbeth and his friend Banquo, returning victorious from battle, are waylaid by three witches. The witches greet Macbeth with a prophecy. They say that he shall be king hereafter. As an ambitious warrior, the prospect is a good one, or is it? Macbeth ruminates:

If good, why do I yield to that suggestion, Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair and make my seated heart knock at my ribs, against the use of nature.There is something so tantalising, tempting and terrifying about the witches' prophecy. It appeals to Macbeth's vaulting ambition, but it is also destabilising. Before the prophecy he was a reasonably high-ranking thane, and he was probably expecting no more from life (there was limited social mobility in Scotland back then), now he is not so sure. After all, the prophecy is no more than a glimpse of a possible future, the road that will take him there is unclear.

He sends word of the prophecy to his wife (Lady Macbeth). She too is tempted but she also sees clearly the path to the future:

Thy letters have transported me beyond this ignorant present, and I feel now the future in an instant.The path will require the murder of the present king.

The deed is carried out, but then Macbeth realises that the glorious future he imagined is never quite secure: his kingship is illegitimate and unnatural, he must continually fight off potential threats. In short, more blood must be spilled. Macbeth has become trapped by an imagined future.

The most startling illustration of Macbeth's uneasy relationship with the future comes with the murder of his friend Banquo. Banquo had also received a prophecy from the witches. He was told that although he would not be king, he would "beget" kings. Indeed, his seed would give rise to a whole dynasty. Macbeth cannot allow this, and tries to have Banquo and his son killed. Banquo is dispatched, but the son escapes.

It was pointed out to me that Macbeth's desire to prevent Banquo begetting a dynasty is odd. There is no mention in the play of Macbeth's children. They are conspicuous by their absence. So there is no realistic prospect of Macbeth having his own lineage. He must surely know that his kingship will be an ephemeral and temporary thing? Something to be enjoyed while it lasts.

But he cannot seem to accept this; he is always fighting the future.

Out Damned Spot

It is not just the future that is a problem for Macbeth, the past is also an issue. Macbeth thinks that the murder of the king will be a one-off event, something that can be done and then forgotten about:

If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere well it were done quickly.But just as imagination provides a conduit to the future, memory provides a conduit to the past. And Macbeth's memories of the dreadful deeds he has performed to become king stalk his every step. Perhaps the most famous illustration is the scene in which the bloody ghost of Banquo interrupts Macbeth when he is having a banquet.

And it is not just Macbeth who is haunted by the past; his wife suffers more than he. This is exquisitely portrayed in her sleepwalking scene. She is constantly rubbing her hands, trying to get rid of the bloodstains that she remembers from the murder of the king.

Out damned spot! Out, I say!... Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him.In short, both Macbeth and his wife were tempted by an imagined future and haunted by a remembered past.

The Brief Candle

No discussion of the role of time in Macbeth would be complete without mentioning the famous last soliloquy. And mentioning this segues neatly with what I was just talking about.

Lady Macbeth eventually loses her battle with sanity and kills herself. Macbeth is told of this by his trusty aide Seyton and it prompts the following reflection:

She should have died hereafter. There would have been a time for such a word. Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow creeps in this petty pace from day to day to the last syllable of recorded time, and all our yesterdays have lighted fools the way to dusty death. Out, out brief candle. Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more. It is a tale, told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.This passage is truly beautiful. An example of the soaring literary heights that Shakepeare can reach. It almost needs no commentary, but I can't help myself.

I think this passage signifies Macbeth's mature understanding of time. He began the play with a naive understanding of time. He was tempted by an imagined future, and tricked into thinking this would be easy to obtain. He eventually realised the errors of his ways: the future is never secure and the past can never be escaped. He now sees that he has lost the battle with time: he made the wrong choices and failed to make his life a unified, and meaningful narrative.

Now, this final soliloquy could, of course, be interpreted as a global pessimism about human life. That it is short, petty and signifies nothing, and that this is true of all people. I think it is better to see it as connected directly to Macbeth's choices, and that life can be fulfilling if we reject Macbeth's naivete.

This is a theme I will be exploring in more depth in my series on the Divine Comedy's Promenade.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Oppy on Moral Arguments (Part 9): The Argument from Convergence

This post is part of my series on Graham Oppy's discussion of moral arguments. For an index, see here.

The Argument Stated

The ninth argument covered by Oppy is a neglected historical oddity. It is attributed to Henry Sidgwick (who did not endorse it) and is known as the argument from convergence. Take a look:

Anyway, there is no need to wax lyrical on it for too long, we need to know whether the argument is successful.

Analysis

Sidgwick rejected the conclusion of this argument for one simple reason: he thought it more likely that there was a fundamental irreconcilable tension in the faculty of practical reason, than that there was a God to reconcile them. I tend to agree.

Oppy notes, as I did a moment ago, that the argument equivocates between prudential reason and moral reason. One way to resolve the tension is to reduce moral reasons to prudential reasons or vice versa. Many secular theories of morality do this. For example, Hobbes reduced moral reasons to prudential reasons of a particular sort.

The Argument Stated

The ninth argument covered by Oppy is a neglected historical oddity. It is attributed to Henry Sidgwick (who did not endorse it) and is known as the argument from convergence. Take a look:

- (P1) What I have most reason to do is what will best secure my own happiness.

- (P2) What I have most reason to do is what morality requires.

- (P3) If there is no moral government of the universe, then what will best secure my happiness is not always what morality requires.

- (C1) Therefore, there is a moral government of the universe.

- (C2) Therefore, there is an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

Anyway, there is no need to wax lyrical on it for too long, we need to know whether the argument is successful.

Analysis

Sidgwick rejected the conclusion of this argument for one simple reason: he thought it more likely that there was a fundamental irreconcilable tension in the faculty of practical reason, than that there was a God to reconcile them. I tend to agree.

Oppy notes, as I did a moment ago, that the argument equivocates between prudential reason and moral reason. One way to resolve the tension is to reduce moral reasons to prudential reasons or vice versa. Many secular theories of morality do this. For example, Hobbes reduced moral reasons to prudential reasons of a particular sort.

Friday, January 29, 2010

Oppy on Moral Arguments (Part 8): The Argument from Conscience

This post is part of my series on Graham Oppy's discussion of moral arguments. For an index, see here.

The Argument Stated

The eighth argument dealt with by Graham Oppy is the argument from conscience. Something like this seems to lie behind many religious believers acceptance of a moral law. The argument has the following form:

The Argument Stated

The eighth argument dealt with by Graham Oppy is the argument from conscience. Something like this seems to lie behind many religious believers acceptance of a moral law. The argument has the following form:

- (P1) Conscience, as a sanction of right conduct, induces feelings and experiences of fear, shame and responsibility.

- (P2) Such feelings require a person who is their 'focus', that is, a person to whom one is responsible, before whom one is ashamed and so on.

- (P3) No human being can systematically be the focus for these feelings.

- (C1) Therefore, conscience logically requires a relationship to an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

- (C2) Therefore, there is an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

Reading that cannot help but evoke H.L. Mencken's immortal words: "Conscience is the inner voice that warns us somebody might be looking."

Let's see whether we can beat Mencken's mordant wit.

Analysis

Beginning with P1, we have to ask about the ontological status of conscience. It seems that it is simply a label for a cluster of emotions or feelings we have about our own conduct. We need to be clear that this is the meaning being employed because some might argue that conscience is mystical or sui generis. Understood as a label for a cluster of emotions, "conscience" clearly exists.

Moving to P2, we must ask whether it is true that conscience requires a personal focus. Could there not be a general, untethered sense of guilt just as there can be a directionless feeling of anger or a vague sense of unease?

Maybe this is not a good objection, but it is worth considering. More substantive is the question about the need for a single person to play the role of the focus. Why not many different people, at different times? There seems to be no good answer to that question.

P3 is perhaps the most dubious of all (at least from my perspective). Oppy does not pursue the matter in great detail (he speaks only of the plausibility of a naturalistic explanation for conscience), but I am pretty sure that there is one person, who is not God, who can be the focus: yourself. If we adopt a transtemporal theory of self, i.e. a view based on the idea that the self exists through time, there is no difficulty with believing that you can have certain expectations of your own conduct at T1 which you fail to live up to at T2 and which thereby induce feelings of guilt or shame at T3. (See Ainslie's The Breakdown of the Will for some of the theoretical basis for this).

Analysis

Beginning with P1, we have to ask about the ontological status of conscience. It seems that it is simply a label for a cluster of emotions or feelings we have about our own conduct. We need to be clear that this is the meaning being employed because some might argue that conscience is mystical or sui generis. Understood as a label for a cluster of emotions, "conscience" clearly exists.

Moving to P2, we must ask whether it is true that conscience requires a personal focus. Could there not be a general, untethered sense of guilt just as there can be a directionless feeling of anger or a vague sense of unease?

Maybe this is not a good objection, but it is worth considering. More substantive is the question about the need for a single person to play the role of the focus. Why not many different people, at different times? There seems to be no good answer to that question.

P3 is perhaps the most dubious of all (at least from my perspective). Oppy does not pursue the matter in great detail (he speaks only of the plausibility of a naturalistic explanation for conscience), but I am pretty sure that there is one person, who is not God, who can be the focus: yourself. If we adopt a transtemporal theory of self, i.e. a view based on the idea that the self exists through time, there is no difficulty with believing that you can have certain expectations of your own conduct at T1 which you fail to live up to at T2 and which thereby induce feelings of guilt or shame at T3. (See Ainslie's The Breakdown of the Will for some of the theoretical basis for this).

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Unicode nearing 50% of the web

About 18 months ago, we published a graph showing that Unicode on the web had just exceeded all other encodings of text on the web. The growth since then has been even more dramatic.

Web pages can use a variety of different character encodings, like ASCII, Latin-1, or Windows 1252 or Unicode. Most encodings can only represent a few languages, but Unicode can represent thousands: from Arabic to Chinese to Zulu. We have long used Unicode as the internal format for all the text we search: any other encoding is first converted to Unicode for processing.

This graph is from Google internal data, based on our indexing of web pages, and thus may vary somewhat from what other search engines find. However, the trends are pretty clear, and the continued rise in use of Unicode makes it even easier to do the processing for the many languages that we cover.

Searching for "nancials"?

Unicode is growing both in usage and in character coverage. We recently upgraded to the latest version of Unicode, version 5.2 (via ICU and CLDR). This adds over 6,600 new characters: some of mostly academic interest, such as Egyptian Hieroglyphs, but many others for living languages.

We're constantly improving our handling of existing characters. For example, the characters "fi" can either be represented as two characters ("f" and "i"), or a special display form "fi". A Google search for [financials] or [office] used to not see these as equivalent — to the software they would just look like *nancials and of*ce. There are thousands of characters like this, and they occur in surprisingly many pages on the web, especially generated PDF documents.

But no longer — after extensive testing, we just recently turned on support for these and thousands of other characters; your searches will now also find these documents. Further steps in our mission to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful.

And we're angling for a party when Unicode hits 50%!

Posted by Mark Davis, Senior International Software Architect

Web pages can use a variety of different character encodings, like ASCII, Latin-1, or Windows 1252 or Unicode. Most encodings can only represent a few languages, but Unicode can represent thousands: from Arabic to Chinese to Zulu. We have long used Unicode as the internal format for all the text we search: any other encoding is first converted to Unicode for processing.

This graph is from Google internal data, based on our indexing of web pages, and thus may vary somewhat from what other search engines find. However, the trends are pretty clear, and the continued rise in use of Unicode makes it even easier to do the processing for the many languages that we cover.

Searching for "nancials"?

Unicode is growing both in usage and in character coverage. We recently upgraded to the latest version of Unicode, version 5.2 (via ICU and CLDR). This adds over 6,600 new characters: some of mostly academic interest, such as Egyptian Hieroglyphs, but many others for living languages.

We're constantly improving our handling of existing characters. For example, the characters "fi" can either be represented as two characters ("f" and "i"), or a special display form "fi". A Google search for [financials] or [office] used to not see these as equivalent — to the software they would just look like *nancials and of*ce. There are thousands of characters like this, and they occur in surprisingly many pages on the web, especially generated PDF documents.

But no longer — after extensive testing, we just recently turned on support for these and thousands of other characters; your searches will now also find these documents. Further steps in our mission to organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful.

And we're angling for a party when Unicode hits 50%!

Posted by Mark Davis, Senior International Software Architect

Oppy on Moral Arguments (Part 7): The Argument from Heavenly Reward

This post is part of my series on Graham Oppy's discussion of moral arguments. For an index, see here.

The Argument Stated

The seventh argument to get the Oppy-treatment is the argument from heavenly reward. This is a presumptuous argument with the following form:

The Argument Stated

The seventh argument to get the Oppy-treatment is the argument from heavenly reward. This is a presumptuous argument with the following form:

- (P1) People who fail to believe in an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god are guaranteed to miss out on the benefits of infinite heavenly reward.

- (P2) No sensible person chooses to miss out on the benefits of infinite heavenly reward.

- (C1) Therefore, every sensible person believes in an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

- (P3) What every sensible person believes cannot be false.

- (C2) Therefore, there is an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

This must have been cooked-up in some theistic genetics laboratory. It is a strange hybrid of Pascal's wager and an argument from authority. Is this new creature any less troubling than its fallacious forebears? Let's find out.

Analysis

P1 assumes what needs to be proved. The argument is trying to establish the existence of God from certain moral considerations, but right there in P1 is the assumption that God exists ("those who fail to believe...are guaranteed...". Furthermore, it assumes that one particular interpretation of God's justice is true, namely: that he will punish wrongdoers forever. Even some Christians are willing to doubt this.

In addition to this, the argument assumes we have access to the "secret handshake" that gets us into heaven. But different religious sects have different understandings of this secret handshake forcing us into a type of moral epistemological nihilism. Thus, the pragmatic appeal of the argument is lessened.

Finally, P3 is not obviously true. There seems to be no reason to accept that sensible (by which is meant "prudent" in this argument) people have true beliefs.

P1 assumes what needs to be proved. The argument is trying to establish the existence of God from certain moral considerations, but right there in P1 is the assumption that God exists ("those who fail to believe...are guaranteed...". Furthermore, it assumes that one particular interpretation of God's justice is true, namely: that he will punish wrongdoers forever. Even some Christians are willing to doubt this.

In addition to this, the argument assumes we have access to the "secret handshake" that gets us into heaven. But different religious sects have different understandings of this secret handshake forcing us into a type of moral epistemological nihilism. Thus, the pragmatic appeal of the argument is lessened.

Finally, P3 is not obviously true. There seems to be no reason to accept that sensible (by which is meant "prudent" in this argument) people have true beliefs.

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Google's Privacy Principles

Thursday, January 28th marks International Data Privacy Day. We're recognizing this day by publicly publishing our guiding Privacy Principles.

We've always operated with these principles in mind. Now, we're just putting them in writing so you have a better understanding of how we think about these issues from a product perspective. Like our design and software guidelines, these privacy principles are designed to guide the decisions we make when we create new technologies. They are one of the key reasons our engineers have worked on new privacy-enhancing initiatives and features like the Google Dashboard, the Ads Preferences Manager and the Data Liberation Front. And there is more in store for 2010.

You can find out more about our efforts at the Google Privacy Center and on our YouTube channel.

Posted by Alan Eustace, Senior Vice President, Engineering & Research

- Use information to provide our users with valuable products and services.

- Develop products that reflect strong privacy standards and practices.

- Make the collection of personal information transparent.

- Give users meaningful choices to protect their privacy.

- Be a responsible steward of the information we hold.

We've always operated with these principles in mind. Now, we're just putting them in writing so you have a better understanding of how we think about these issues from a product perspective. Like our design and software guidelines, these privacy principles are designed to guide the decisions we make when we create new technologies. They are one of the key reasons our engineers have worked on new privacy-enhancing initiatives and features like the Google Dashboard, the Ads Preferences Manager and the Data Liberation Front. And there is more in store for 2010.

You can find out more about our efforts at the Google Privacy Center and on our YouTube channel.

Posted by Alan Eustace, Senior Vice President, Engineering & Research

Supporting students from under-represented backgrounds in the pursuit of a technical education

(Cross-posted with the Google Students Blog)

We know firsthand how vital a good science or math education is to building products that change the world and enrich peoples' lives. We're committed to supporting students in their pursuit of the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields — particularly those from traditionally under-represented backgrounds.

Over time, we've dedicated time, people, and financial resources to organizations, events and schools to help advance this mission — and we're excited to share that we rounded out 2009 with a donation of $8 million to a variety of organizations who share our dedication to this cause. Our efforts were focused in four key areas:

Starting in high school

STEM education at an elementary and high school level builds technical skills early and encourages interest in technology. To support the ongoing education of these subjects, we identified more than 600 high schools with significant populations of students from under-represented and economically disadvantaged backgrounds and are providing laptops to their computer science and math departments. We are also offering laptops to some of the most promising students in these schools. In a time when many of these schools are experiencing decreased funding, we wanted to support their continued commitment to learning and teaching these subjects, and recognize the exceptional work done by teachers in these communities. If you're interested in learning more about our efforts in this field, check out Google Code University (CS tutorials for students and teachers) as well as our tools, tips and lesson plans for K-12 educators.

Growing promising talent

We've worked with over 200 outstanding students as part of our FUSE, CSSI, BOLD and BOLD Practicum summer programs. To help the alumni of our 2009 summer programs pursue their studies, we awarded former program participants with school-based scholarships. We hope that this support for tuition will lessen the financial burden on these students and their families, reduce work-study commitments and free them up to explore other educational opportunities, like studying abroad.

Advancing technical knowledge through universities

We have close relationships with universities around the world — not only do we employ their alumni, but they are also a source of groundbreaking research and innovation. We awarded grants ranging in size from $20k to $100k to 50 U.S.-based universities with whom we already have relationships and directed these funds toward departments that are closely aligned with promoting under-represented minorities in technology. We hope to expand this effort both to more U.S.-based universities and to universities around the world in the future.

Partnerships with the organizations that make it happen

Our commitment to promote women and under-represented minorities in technology is shared by dozens of local and national organizations around the country. We awarded grants to 22 partner organizations, almost all of which we have worked with in the past. These organizations are on the front lines, making sure that under-represented groups have the support, resources and contacts they need. You'll find a list of these organizations with a quick overview of the work they focus on here.

This was a terrific way to close out 2009 and we look forward to attracting and encouraging more students from traditionally under-represented backgrounds to pursue studies and careers in science, technology, engineering and math. In the meantime, you can find news especially for students on the Students Blog and by following us on @googlestudents.

Posted by Shannon Deegan, Director, People Operations

Search is getting more social

Late last year we released the Social Search experiment to make search more personal with relevant web content from your friends and online contacts. We were excited by the number of people who chose to try it out, and today Social Search is available to everyone in beta on google.com.

We've been having a lot of fun with Social Search. It's baby season here on our team — two of us just had little ones, and a third is on the way. We're all getting ready to be parents for the first time and we have lots of questions. So, what do we do? We search Google, of course! With Social Search, when we search for [baby sleep patterns], [swaddling] or [best cribs], not only do we get the usual websites with expert opinions, we also find relevant pages from our friends and contacts. For example, if one of my friends has written a blog where he talks about a great baby shop he found in Mountain View, this might appear in my social results. I could probably find other reviews, but my friend's blog is more relevant because I know and trust the author.

While we've been enjoying Social Search (and having babies), we've been hard at work on new features. For example, we've added social to Google Images. Now when you're doing a search on Images, you may start seeing pictures from people in your social circle. These are pictures that your friends and other contacts have published publicly to the web on photo-sharing sites like Picasa Web Albums and Flickr. Just like the other social results, social image results appear under a special heading called "Results from your social circle." Here's what it looks like:

Looking at the screenshot, you may notice two new links for "My social circle" and "My social content." These links will take you to a new interface we've added where you can see the connections and content behind your social results. Clicking on "My social circle" shows your extended network of online contacts and how you're connected.

Looking at the screenshot, you may notice two new links for "My social circle" and "My social content." These links will take you to a new interface we've added where you can see the connections and content behind your social results. Clicking on "My social circle" shows your extended network of online contacts and how you're connected.

Clicking on "My social content" lists your public pages that might appear in other people's social results. This new interface should give you a peek under the hood of how Social Search builds your social circle and connects you with web content from your friends and extended network. You can check out your social circle directly by visiting this link. (Note that it may take some time for the connections and content to update.)

We think there's tremendous potential for social information to improve search, and we're just beginning to scratch the surface. We're leaving a "beta" label on social results because we know there's a lot more we can do. If you want to get the most out of Social Search right away, get started by creating a Google profile, where you can add links to your other public online social services. Check out this short video to learn more:

The new features are rolling out now on google.com in English for all signed-in users, and you should start seeing them in the next few days. Time to socialize!

Posted by Maureen Heymans, Technical Lead for Social Search, and Terran Melconian, Technical Lead for Social Image Search

We've been having a lot of fun with Social Search. It's baby season here on our team — two of us just had little ones, and a third is on the way. We're all getting ready to be parents for the first time and we have lots of questions. So, what do we do? We search Google, of course! With Social Search, when we search for [baby sleep patterns], [swaddling] or [best cribs], not only do we get the usual websites with expert opinions, we also find relevant pages from our friends and contacts. For example, if one of my friends has written a blog where he talks about a great baby shop he found in Mountain View, this might appear in my social results. I could probably find other reviews, but my friend's blog is more relevant because I know and trust the author.

While we've been enjoying Social Search (and having babies), we've been hard at work on new features. For example, we've added social to Google Images. Now when you're doing a search on Images, you may start seeing pictures from people in your social circle. These are pictures that your friends and other contacts have published publicly to the web on photo-sharing sites like Picasa Web Albums and Flickr. Just like the other social results, social image results appear under a special heading called "Results from your social circle." Here's what it looks like:

Looking at the screenshot, you may notice two new links for "My social circle" and "My social content." These links will take you to a new interface we've added where you can see the connections and content behind your social results. Clicking on "My social circle" shows your extended network of online contacts and how you're connected.

Looking at the screenshot, you may notice two new links for "My social circle" and "My social content." These links will take you to a new interface we've added where you can see the connections and content behind your social results. Clicking on "My social circle" shows your extended network of online contacts and how you're connected.

Clicking on "My social content" lists your public pages that might appear in other people's social results. This new interface should give you a peek under the hood of how Social Search builds your social circle and connects you with web content from your friends and extended network. You can check out your social circle directly by visiting this link. (Note that it may take some time for the connections and content to update.)

We think there's tremendous potential for social information to improve search, and we're just beginning to scratch the surface. We're leaving a "beta" label on social results because we know there's a lot more we can do. If you want to get the most out of Social Search right away, get started by creating a Google profile, where you can add links to your other public online social services. Check out this short video to learn more:

The new features are rolling out now on google.com in English for all signed-in users, and you should start seeing them in the next few days. Time to socialize!

Posted by Maureen Heymans, Technical Lead for Social Search, and Terran Melconian, Technical Lead for Social Image Search

Table of Contents

This is a table of contents for the blog. I have organised it into different categories of philosophy. There is some overlap between them.

General

- What Good is an Explanation (Peter Lipton) Part 1, Part 2

- Explanations: A Gentle Introduction

- Explanations: Breadth and Depth

- Theism and Explanation by Gregory Dawes

- Neuroscientific Explanations with Carl Craver

- Evidence and Evolution

- Causal Models

- Oppy on Disagreement Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Moral Philosophy

- Blackwell Companion to Ethics

- The Dialectical Necessity of Morality

- Oppy on Moral Arguments

- Wes Morriston on Theistic Morality

- Why be Moral?

- Hobbes's Moral Theory

- Maitzen on Morality and Atheism

- Hume on Morality

- Wielenberg on Morality

- Metaethical Constructivism with Sharon Street

- The Epistemological Challenge to Metanormative Realism (Enoch) Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

- The Non Existence of God by Nicholas Everitt

- C.S Lewis and the Search for Rational Religion by John Beversluis

- Oppy on Moral Arguments

- Wes Morriston on Theistic Morality

- Why be Moral?

- Hume on Religion

- Maitzen on Morality and Atheism

- Wielenberg on Morality

- Posts on Common Sense Atheism

- Gwiazda on Swinburne

- The End of Skeptical Theism

Law and Society

- Promenade by the Divine Comedy

- Shakespeare's Philosophy

- Shakespeare's Comedies (under construction)

Evidence and Evolution (Index)

One of the more rewarding books to cross my desk in the past year was Elliot Sober's Evidence and Evolution. The name might be deceptive: this is not an easy-to-read book setting out various bits of evidence for evolution (like Jerry Coyne's Why Evolution is True); this is a long, technical and difficult book on epistemology and the philosophy of science.

It was rewarding because it introduced me to a new way of looking at certain issues. Prior to reading Sober, I was a bit of Bayes-virgin. I have now been engrossed in the topic for six months or so (I'm still little more than a dabbler).

Sober covers four topics in what are really four separate books:

- The different statistical tools we can use to assess theories (Bayesianism, Likelihoodism, and Frequentism).

- Intelligent Design (focusing a lot on the correct formulation of the design argument and the testability of hypotheses).

- Natural Selection (comparing it to other theories of evolutionary change).

- Common Ancestry (testing the theory of branching descent).

As a good philosopher, Sober reaches no firm conclusions on any of these topics.

I am going to do occasional posts on this book. I will not go through it in the same detail as I am doing with other books on this blog. That said, I am going to take a considerable whack at the chapter on Intelligent Design simply because it straddles two of my own interests: philosophy of science and religious philosophy. I am also going to use some of the material from chapter one in a series covering Bayes Theorem.

I am going to do occasional posts on this book. I will not go through it in the same detail as I am doing with other books on this blog. That said, I am going to take a considerable whack at the chapter on Intelligent Design simply because it straddles two of my own interests: philosophy of science and religious philosophy. I am also going to use some of the material from chapter one in a series covering Bayes Theorem.

I will take this at a fairly leisurely pace. This is a book to be savoured and chewed-over, not gulped down at one sitting.

Anyway, this post will, eventually, serve as an index for all others.

Dead Rising 2 Survival Horror Video Games

Evidyon, HackWars, and SlothRPG: FreeGamer MMO Time!

So, here we go! First post from scary old uncle TheAncientGoat ;)

Evidyon, MMO from Reddit-way

Evidyon is an interesting 3D MORPG recently gone Open Source under the advice of the reddit community, releasing a whole slew of content, tutorials and documentation of how they went about making it in the process. This is a very admirable move, we'll all agree, so show them some love. Unfortunately, it's windows only, relying on DirectX (not VB though, thanks for the fix Nerrad), and I haven't gotten it running under Wine as of yet, but hopefully a few smart alecs can help port it.

Like most other mmo's it has a fantasy setting, as you can see in the screenshot and video, it also sports a Diabloesque style of combat

HackWars: MMO where you craft by programming

Here's one for you scriptmonkies, Hackwars, a Java MMO where you play as a hacker (or cracker, more accurately), breaking into pcs by attacking their ports for massive damage. An interesting aspect of this game is its crafting system, you program your own programmes, either in Javascript or the game's built in HackScript, to make scripts that either help you fight or just entertain you. It has both a 2d and 3d interface.

This was also found via reddit and the author wrote some pretty interesting commentary on developing such a game (which you'll see if you follow that link). Also, why not post upcoming FOSS games on our little corner of redditOpenSourceGames and we'll try and cover them if we have the time.

SlothRPG

SlothRPG is a fantasy 2D MUD -like RPG, also written in Java. It has recently been re-invigorated, so it's worth checking for updates. Unfortunately it doesn't have any servers online at the moment, so you'll have to host your own if you want to check it out

News: Left 4 Dead 2 updates!

I've been super quiet of late, only because I'm flying around the universe, saving humans and aliens, tagging bad guys, and getting the chicks in Mass Effect 2. Taking my time, so expect a review awhile later. For now, Left 4 Dead 2 is getting some interesting updates!

---

The Passing is apparently coming "soon", and as you know with Valve, that can mean anytime from now to eternity. The Passing is the really interesting DLC planned for L4D2 in which survivors of the first game meet up with survivors of the 2nd. What happens next is really a mystery. I'm thinking.... TEAM DEATHMATCH with perks and kill-streaks and.... whoops, wrong game.

Anyway, The Passing is a while off but the one that's coming quite soon (in a few weeks, says reports) will be a major addition of Infected bots for Versus mode. This is really, really good because it's an annoyance when people drop during matches leaving teams unbalanced. It may even give players the opportunity to practice their Hunter pounces and stake out strategic hotspots for the next competitive game.

There's also a tweak to remove auto-spawning for Infected side during finales. Apparently, auto-spawning brings the average survival rate of Survivor teams to finish the game at a low of 34.56% Valve thinks that's wayyy too low and not enough fun for people playing the Survivors.

All good stuff if you're still keeping one eye on Valve to see that they are living up to their promise of continual support and updates to Left 4 Dead and its sequel. Me? I'm kinda' tired of the game. Once you've written an 8000 word thesis on it and played it to bits, you go, "Meh, there are a bunch of other stuff out there to try anyway." And I want them to start focusing on making Half-Life 2: Episode 3.

Finally, I don't know if it's the same anywhere else, but one thing that never fails to amaze me is how tons of girls in Singapore play Left 4 Dead 2?!? They even fit it into their daily routines of pedicures and shopping. Girls-night-out can actually be fun times at a LAN shop. What is the world coming to?

Oppy on Moral Arguments (Part 6): The Argument from the Costs of Irreligion

This post is part of my series on Graham Oppy's discussion of moral arguments. For an index, see here.

The Argument Stated

The sixth argument that Oppy looks at often comes up in non-philosophical conversations. It is the argument from the costs of irreligion. It looks something like the following:

The Argument Stated

The sixth argument that Oppy looks at often comes up in non-philosophical conversations. It is the argument from the costs of irreligion. It looks something like the following:

- (P1) Loss of belief in God has coincided with a rise in social evils: divorce, murder, lack of respect for authority and so on.

- (C1) Therefore, loss of belief in God is the cause of modern social evils.

- (C2) Therefore, we should all return to belief in an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

- (P2) One cannot have an obligation to adopt false beliefs.

- (C3) Therefore, there is an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

There is always going to be something fishy about an argument with three conclusions drawn from only two premises: it is likely that unwarranted or suspect inferences are being made. Let's see if we can pinpoint those suspect inferences.

Analysis

This one could be thrashed out for hours, with numerous stats and historical examples being offered by both sides.

First off, Oppy thinks we may have reason to doubt the very idea that there has been a rise in unbelief. Given that it was often dangerous to profess unbelief in the past, it may be that the recent increase is simply due to a more tolerant social environment. Oppy doesn't go beyond a mere suggestion, but Jennifer Hecht's book Doubt: A History shows that religious scepticism has a long and noble tradition.

Second, Oppy thinks there is no clear evidence to suggest that the world is getting worse. Some, like Steven Pinker, have argued that things are getting better. A rhetorical question might help to underline the point: if God gave you a choice to live at any other moment in history, would you choose pious Medieval Europe, wracked by plague, corruption, torture, witch-hunting and war? Oppy argues it is unlikely that you would.

Let's concede the first premise. It still does not follow that unbelief causes social evils. Correlation does not prove causation, as people are fond of reminding us. Other factors may be causally relevant, e.g. massive increase in population, increasing urbanisation (a good predictor of crime). There is no non-question-begging reason to causally link unbelief with the rise in social evils.

One could push this further by arguing that an increase in belief would only add fuel to fire. The world is a melting pot of different religious beliefs and fundamentalisms. Getting more people to believe might simply accentuate the latent conflict in ideologies.

Finally, the jump from P2 to C3 is chasm-like in proportions. There are different senses of obligation, and no reason to suspect that a moral obligation must be based on true beliefs. I covered this earlier in the series.

First off, Oppy thinks we may have reason to doubt the very idea that there has been a rise in unbelief. Given that it was often dangerous to profess unbelief in the past, it may be that the recent increase is simply due to a more tolerant social environment. Oppy doesn't go beyond a mere suggestion, but Jennifer Hecht's book Doubt: A History shows that religious scepticism has a long and noble tradition.

Second, Oppy thinks there is no clear evidence to suggest that the world is getting worse. Some, like Steven Pinker, have argued that things are getting better. A rhetorical question might help to underline the point: if God gave you a choice to live at any other moment in history, would you choose pious Medieval Europe, wracked by plague, corruption, torture, witch-hunting and war? Oppy argues it is unlikely that you would.

Let's concede the first premise. It still does not follow that unbelief causes social evils. Correlation does not prove causation, as people are fond of reminding us. Other factors may be causally relevant, e.g. massive increase in population, increasing urbanisation (a good predictor of crime). There is no non-question-begging reason to causally link unbelief with the rise in social evils.

One could push this further by arguing that an increase in belief would only add fuel to fire. The world is a melting pot of different religious beliefs and fundamentalisms. Getting more people to believe might simply accentuate the latent conflict in ideologies.

Finally, the jump from P2 to C3 is chasm-like in proportions. There are different senses of obligation, and no reason to suspect that a moral obligation must be based on true beliefs. I covered this earlier in the series.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

Oppy on Moral Arguments (Part 5): The Argument from the Need for Justice

This post is part of my series on Graham Oppy's discussion of moral arguments. For an index, see here.

The Argument Stated

The fifth argument that Oppy covers is a popular one: the argument from the need for justice. It has the following form:

The Argument Stated

The fifth argument that Oppy covers is a popular one: the argument from the need for justice. It has the following form:

- (P1) Virtue is not always rewarded in this life.

- (P2) Justice demands that virtue is always rewarded in the end.

- (C1) Therefore, there is an afterlife in which an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god ensures that the virtuous are rewarded.

- (C2) Therefore, there is an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

There is a correlative version of this argument that replaces "virtue" with "vice", and "reward" with "punishment".

The argument is nothing more than wishful-thinking, but this means that it has a strong emotional appeal. Let's see what can be done to smother its appeal.

Analysis

P1 is largely uncontroversial. However, we would need to pin down or settle upon a definition of virtue and vice. This should not be too difficult, so we can leave it to one side.

The main problem with the argument comes in P2. On a technical level, Oppy thinks it is ambiguous because it does not differentiate between individual acts of virtue and a lifetime of virtue. Here's the problem: in the course of your life you do many good and bad things. Surely when we demand that virtue is rewarded and vice is punished we only mean the net sum of virtue over vice over one lifetime should be rewarded, and not each individual act? Oppy, at least, thinks this would be a better way of putting it.

Accepting this reformulation, it is still not at all clear why virtue needs to be rewarded. Beyond a mere wish that this be the case, there are no sound arguments linking virtue and reward. There is certainly no logical connection between virtue and reward. And many moral theories reject the idea, preferring to say virtue is its own reward.

In any case, there is massive leap from P2 to P3. Just because we would like virtue to be rewarded does not mean that it must be rewarded. In particular, it does not mean that there is some afterlife where this takes place. From observable evidence, the best inference to make is that our universe is morally imperfect. Theists might argue that there are good independent reasons for believing in an afterlife (they always do this!) but that cannot be proved in this argument.

Finally, even if we accept that virtue must be rewarded, there are alternative metaphysical schemes in which this is the case -- e.g. karma and reincarnation -- and which do not support the existence of an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

P1 is largely uncontroversial. However, we would need to pin down or settle upon a definition of virtue and vice. This should not be too difficult, so we can leave it to one side.

The main problem with the argument comes in P2. On a technical level, Oppy thinks it is ambiguous because it does not differentiate between individual acts of virtue and a lifetime of virtue. Here's the problem: in the course of your life you do many good and bad things. Surely when we demand that virtue is rewarded and vice is punished we only mean the net sum of virtue over vice over one lifetime should be rewarded, and not each individual act? Oppy, at least, thinks this would be a better way of putting it.

Accepting this reformulation, it is still not at all clear why virtue needs to be rewarded. Beyond a mere wish that this be the case, there are no sound arguments linking virtue and reward. There is certainly no logical connection between virtue and reward. And many moral theories reject the idea, preferring to say virtue is its own reward.

In any case, there is massive leap from P2 to P3. Just because we would like virtue to be rewarded does not mean that it must be rewarded. In particular, it does not mean that there is some afterlife where this takes place. From observable evidence, the best inference to make is that our universe is morally imperfect. Theists might argue that there are good independent reasons for believing in an afterlife (they always do this!) but that cannot be proved in this argument.

Finally, even if we accept that virtue must be rewarded, there are alternative metaphysical schemes in which this is the case -- e.g. karma and reincarnation -- and which do not support the existence of an orthodoxly conceived monotheistic god.

Sin and Punishment 2 Popular Shooting Games

What if God Commanded Something Terrible? (Part 4): We Must Obey

This post is part of my series on Wes Morriston's discussions of theistic morality. For an index, see here.

I am currently taking a look at a paper by Morriston entitled "What if God Commanded Something Terrible?". The paper looks at theistic responses to the problems inherent in a divine command theory (DCT) of morality.

Part One set out why it is a problem for DCT-proponents that God could command us to do something terrible. Part Two examined a classic theistic response to this problem: claim that God is essentially good and so could never command something terrible. This response was found to be deficient.

Part Three looked at Robert Adams's attempt to proffer a modified DCT. This modification would allow for DCTs to be the best theories of objective morality, while at the same time allowing us to disobey certain commands. This response was found to be confused.

In this part, we consider the third and final response to the problem with the DCT. This third response "bites the bullet", so to speak. It claims that the DCT is sound and that we would have to obey God's command no matter how repugnant it seemed. Let's see if this response fairs any better than its predecessors.

Torturing Children: Yes or No?

Morriston focuses his discussion on the writings of James D. Rissler*. Rissler argues we should not be so quick to rely on our moral intuitions about certain matters such as child torture. If we can conceive of a God who is omnipotent and omniscience, then it seems possible that He could have moral reasons for issuing abhorrent commands that are beyond our ken. In effect, Rissler is appealing to God's "wholly other" nature, a topic discussed in Part One.

Rissler argues that you may have an obligation to torture a child if two conditions are met:

- You are psychologically certain that God has issued this command. This means you have explored all alternative explanations and have found you cannot doubt the veracity and source of the command.

- Although you are unable to conceive of a reason for this command, you can at least conceive of the possibility that God has some good reason for it.

It may be that this sets the bar very high since it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which both conditions are met (surely a belief in one's own insanity is more rational than a belief in the command?). But Rissler thinks God, if he exists, could easily satisfy these conditions.

He does, however, envisage one scenario in which it would be impossible to satisfy the second condition. This would be when the command completely undermines all my pre-existing moral convictions. Imagine your moral convictions form a densely intertwined web. If the command is such that is destroys the entire web, it cannot be obeyed; if it possible to jump to some other part of the web while considering the command, it can be obeyed.

It is difficult to say whether or not the specific example of child torture shows that Rissler's exception is easily met or easily dismissed. Morriston thinks that Rissler's commitment to divine transcendence and epistemic humility would make it easy to accept child torture as a possible good.

In short, on Rissler's theory, it is possible for us to have a moral obligation to torture children.

Third Parties

An interesting aspect of Rissler's theory is its implications for third parties, i.e. those not privy to the divine command. Suppose you are psychologically certain that God commanded you to torture your child. Suppose I stumble upon you in the act of torturing your child. What should I do?

Rissler suggests that I should do everything in my power to stop you. I should not be convinced by your testimony claiming divine permission (or obligation) for what you are doing. Rissler's point seems to be that the individual receiving the command is answerable to god, not to their moral community. And that the moral community is entitled to be sceptical because they would not have psychological certitude concerning the divine command.

But here we get into an interesting debate about the rationality of belief. Rissler thinks that the person in receipt of the command is just as rational in following it, as the moral community are in rejecting it. Morriston thinks this is wrong. He argues that the community's beliefs would override the individual's psychological certainty about the command.

To see this point, Morriston asks us to imagine a detailed example involving a man named "Abe". Abe receives a command from God to torture his child. He has his doubts. He talks it over with his pastor and members of his local church. They are all committed believers and cannot bring themselves to accept that God would issue such a command. Still, Abe cannot shake his belief that God really did issue this command and that God may, given his transcendence, have reasons for doing so.

Morriston argues that the community's scepticism would defeat Abe's belief. The reasoning is as follows:

- Abe is only justified in obeying the command if (a) he psychologically certain that it came from God and (b) God's transcendence makes it conceivable for there to be reason for his issuing the command.

- Abe's church community share his belief in God, including his belief in God's transcendence. They cannot bring themselves to accept that the command came from God.

- Thus, Abe has reason to doubt that (b) has been met, his only reason for obeying the command is (a).

Morriston goes further. In such a case, there would not even be a genuine command. A command can only be successful if it is reasonable to follow it. In the scenario outlined above this reasonability condition is not met.

The funny thing is, Rissler's discussion is designed to deal with the difficult biblical passages where God appears to issue abhorrent commands. But as Morriston points out, these scenarios are very different from the ones discussed by Rissler.

In the Bible, Yahweh backs-up his commands with reasons. For instance, the Canaanite genocide is justified by claiming that the Canaanites were guilty of certain practices, e.g having sex during a woman's menstrual period, homosexuality and bestiality.

In these Bible passages, there is nothing transcendent or "wholly other" about God. His reasons are transparent and all too comprehensible by us lowly humans. Morriston pursues this line of argument at greater length in another paper I will be covering.

*I could not find a personal webpage for Rissler. You can find mention of his papers via a google search.

Monday, January 25, 2010

Extensions, bookmark sync and more for Google Chrome

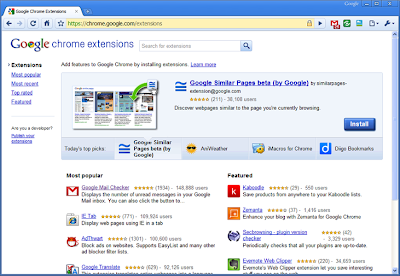

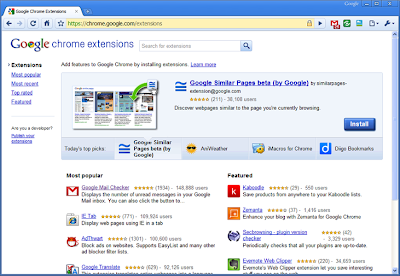

Today we're excited to introduce a new stable release of Google Chrome for Windows, which includes two of the browser's most frequently requested features: extensions and bookmark sync.

Extensions let you add new features and functions to your browser. Some provide one-click access to some of your favorite web applications like eBay and digg, or news and information sources such as NPR and Time.com. Others are useful tweaks for performing common online tasks such as browsing photos, getting directions or shopping.

We previously launched extensions on the beta channel, and many new extensions have since been contributed by developers from all over the world. Now you can browse over 1,500 in our extensions gallery and install them on the stable version of Google Chrome.

Bookmark sync is a handy feature for those of you who use several computers — say, a laptop at work and a desktop at home. You can enable bookmark sync to synchronize your bookmarks on all of your computers so that when you create a bookmark on one computer, it's automatically added across all your computers. This means that you won't need to manually recreate the bookmark each time you switch computers.

You can read more about today's stable release — including performance improvements — on the Google Chrome Blog. Or if you want a look under the hood at what this update means for web developers (including new HTML and Javascript APIs), check out the Chromium blog.

To those using Google Chrome on Linux, extensions are enabled on the beta channel. And for those using Google Chrome for Mac, hang tight — we're working on bringing extensions, bookmark sync and more to the beta soon. Those currently using the stable version for Windows will be automatically updated within the next week (or you can check for updates manually).

If you're on a PC and haven't tried Google Chrome yet, you can download Google Chrome and give all these new features a whirl.

Posted by Nick Baum, Product Manager

Extensions let you add new features and functions to your browser. Some provide one-click access to some of your favorite web applications like eBay and digg, or news and information sources such as NPR and Time.com. Others are useful tweaks for performing common online tasks such as browsing photos, getting directions or shopping.

We previously launched extensions on the beta channel, and many new extensions have since been contributed by developers from all over the world. Now you can browse over 1,500 in our extensions gallery and install them on the stable version of Google Chrome.

Bookmark sync is a handy feature for those of you who use several computers — say, a laptop at work and a desktop at home. You can enable bookmark sync to synchronize your bookmarks on all of your computers so that when you create a bookmark on one computer, it's automatically added across all your computers. This means that you won't need to manually recreate the bookmark each time you switch computers.

You can read more about today's stable release — including performance improvements — on the Google Chrome Blog. Or if you want a look under the hood at what this update means for web developers (including new HTML and Javascript APIs), check out the Chromium blog.

To those using Google Chrome on Linux, extensions are enabled on the beta channel. And for those using Google Chrome for Mac, hang tight — we're working on bringing extensions, bookmark sync and more to the beta soon. Those currently using the stable version for Windows will be automatically updated within the next week (or you can check for updates manually).

If you're on a PC and haven't tried Google Chrome yet, you can download Google Chrome and give all these new features a whirl.

Posted by Nick Baum, Product Manager

Castlevania: Lords of Shadow Video Games Series

What if God Commanded Something Terrible? (Part 3): A Modified DCT

This post is part of my series on Wes Morriston's discussions of theistic morality. For an index, see here.

I am currently working my way through an article by Morriston entitled "What if God Commanded Something Terrible?" -- the question says it all!

Part One explained why this question is a problem for the defender of a divine command theory (DCT) of morality. Part Two dealt with the first theistic response to the problem, which was to claim that God is essentially good and so could never command something terrible. That response was found to be lacking.

This part covers a second theistic response that is developed in the work of Robert M. Adams. Adams defends a modified version of the DCT, one suggesting that we may not always have an obligation to follow God's command.

Upon reading this section of the article for the first time, I was baffled. Either (i) it was late and I was too tired or stupid to concentrate on it; or (ii) Morriston's discussion lacked its usual perspicuity; or (iii) Adams's theory is odd; or (iv) all of the above.

Undeterred, I left it alone for a while and reread it later on. It made more sense the second time, but I was still slightly perplexed at the subtle distinctions being made. This post may well reflect my confusion (and lack of subtlety).

Morality does depend on the Commands of a Good God

Morriston states that Adams himself believes God to be a necessarily existent and essentially good being. Furthermore, Adams thinks a DCT offers the best hope for an objective morality. Thus, he defines morally wrong conduct in terms of contrariety to the commands of a good God. For Adams, God's goodness is fairly stringently defined in terms of a set of properties. Only when God has these properties do his commands issue in moral obligations. This is his modification of DCT

Adams is then willing to consider possible worlds in which God does issue terrible commands (this would be a bad God), and even worlds in which there is no God. He uses the example of a command to sacrifice a child as a reference point.

Adams suggests that if you were to receive such a command, you would have to ask two questions (a) is it still wrong to sacrifice your child? and (b) are you obliged to sacrifice our child? Adams thinks that his modified DCT allows us to answer the second question in the negative. This is because such a command could only come from a bad God.

There is a problem here. Adams thinks morality is dependent on the commands of a good God. If God turns around and issues a command for child sacrifice, then he can no longer be considered good. So, if we got such a command, the objective basis for morality would collapse. This implies that in this possible world, child sacrifice is acceptable, along with everything else.

Morriston points out another troubling implication that arises from Adams's DCT. Since morality is dependent on God's commands, wherever God is silent there is no morality. So if there has been no pronouncement on the propriety of child sacrifice, it is permissible.

There is something slippery about Adams's discussion: he seems to make God dependent on morality at one point (i.e. when saying God must have certain properties), and then he flips and says morality is dependent on God at another point (i.e. when discussing the implications of the command for child sacrifice).

To put this another way, Adams is trying to repossess an already-eaten cake. He is trying to save our intuitions about certain things being wrong, while preserving the dependency of morality on God. It does not seem possible to do this.

Morriston's discusses some other aspects of Adams's theory, but once the points just discussed are made it seems slightly unnecessary. Indeed, Adams's theory does not seem to differ greatly from those considered in Part Two.

Maybe I am being unfair about all of this. Correct me if I am.

Sunday, January 24, 2010

What if God Commanded Something Terrible? (Part 2): Divine Essences

This post is part of my series on Wes Morriston's discussion of theistic morality. For an index, see here.

I am currently looking at an article entitled "What if God Commanded Something Terrible?".

Part One showed why the prospect of God commanding something terrible is problematic for the defender of a Divine Command Theory (DCT). In responding to this problem, the theist can deny that God could command something terrible. This response is usually justified by saying that it is part of God's essential nature to be good.

Morriston identifies three hurdles facing this type of response, let's look at each of them in turn.

1. The Hurdle of Divine Omnipotence

Most defenders of the DCT believe that God is omnipotent. This means that God has the power to do anything that it is logically possible to do. There is nothing logically impossible about commanding something terrible. But then this implies that God would have the ability to command something terrible (indeed, the bible suggests that this was done).

There is a subtle reformulation of omnipotence that may sidestep this hurdle. The theist could say that God has as much power as is compatible with his goodness. So God is all-powerful with respect to his nature.

This sidestep is fine, but it does amount to a rejection of divine omnipotence. To see why this is the case, I invite you to image a being who has all the powers associated with God, but with the additional power to command evil or wicked acts. This being is logically possible and more powerful than God. Therefore, God cannot be omnipotent.

This analysis has two sobering implications. First, it allows for the possibility of an all-powerful evil being. And second, it undermines the rational attraction of theism: why worship a less than omnipotent being?

2. The Hurdle of Divine Transcendence

Sceptical theists might defend DCTs by pointing out that God is "wholly other". God is an eternal, omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent being. We paltry humans are nothing of the sort. We have no right to think that our moral intuitions (about, say, child sacrifices) are correct. Therefore, if God commands us to do something terrible, we can be sure he has morally good reasons for doing so.

One difficulty with this line of argument, especially when we add-in the problem of evil, is that it would seem to mandate a global moral scepticism. Suppose you are a witness to a rape. Should you intervene? Well, if we take the sceptical theist position seriously, we must countenance the possibility that God has a reason for allowing this to take place. Thus, our moral convictions begin to ebb away.

Perhaps we can shore up this deficit by claiming that in the absence of an explicit divine command to the contrary, we should go with our gut feelings. Morriston considers this type of argument later in the article.

3. The Hurdle of Divine Sovereignty

A central wish of theists is for morality to be "up to God". In other words, they deny the possibility of morality without God. This is the doctrine of divine sovereignty. It is simply a redescription of the DCT that underlines the necessary relationship between God's command and the content of our moral beliefs.

If the doctrine of divine sovereignty is challenged, then it will be because there is a standard of goodness independent of God that places restrictions on what he can command. Such a challenge would make God irrelevant to morality. The goal would shift from working out what God commanded, to working out what this independent standard demands.

But those who support the idea that God is essentially good (and so could never command something terrible) are effectively denying divine sovereignty. Remember, God is said to possess certain properties such as omniscience, omnipotence, immateriality, necessity and so on. These properties are defined independently of God. In other words, we do not say that "omniscience is up to God" or "necessity is up to God". Indeed, to say such things would be extremely odd. The same logic applies if we describe God as being essentially good: the property of "goodness" must be defined independently of God.

How often should we clean our Registry

On the Internet, you will find several Web sites promoting the use of Registry programs. These Web sites make you aware of the importance of registry maintenance and how registry programs can simplify the process. However, there is very little information available on how often you need to scan the registry.

Quite often, we hear people asking you to clean up your registry on a daily basis. However, the truth is that there are no specific set norms that control how often you need to clean your Windows Vista registry.

In fact, the frequency of registry repair and clean up activity depends on several factors. For instance, if your computer is new and you do not make any major changes to it, you may not need to perform a registry scan for a long time.

Be Sure to Leave Your Comments! Also be sure to subscribe to my feeds http://feeds.feedburner.com/dotblogger and Follow Me on Googles Friends connection Recommend @lilruth to @MrTweet on Twitter....VOTE FOR ME at http://bloginterviewer.com/animals/dogcents-ruth

Labels:

bloggers,

bloggers. blogs,

blogging,

blogging tips,

blogging. make money computer tips,

make money on line,

registry

Saturday, January 23, 2010

What if God Commanded Something Terrible? (Part 1): The Structure of the Problem

This post is part of my series on Wes Morriston's views on theistic morality. For an index, see here.

We begin with the following article:

A Divine Command Metaethics?

I have said this many times before, but a little repetition never hurt anyone. A moral theory is supposed to give us objective reasons-for-action. That is: reasons for doing or refraining from doing certain things that are somewhat independent of our own subjective preferences (it is easy to get subjective reasons-for-action).

Some religious believers think it is possible to get objective reasons-for-action from God. Specifically, they think that whatever God commands us to do would provide us with an objective reason-for-action. This is the essence of a DCT.

There is one classic objection to DCTs. It can be presented as a terse rhetorical question:

We begin with the following article:

Morriston, W. "What if God Commanded Something Terrible? A Worry for Divine-Command Metaethics" (2009) 45 Religious Studies 249This paper is a great overview of the problems with Divine Command Theories (DCT) of morality. It is available over at Wes's homepage. In this post, I describe the general problem.

A Divine Command Metaethics?

I have said this many times before, but a little repetition never hurt anyone. A moral theory is supposed to give us objective reasons-for-action. That is: reasons for doing or refraining from doing certain things that are somewhat independent of our own subjective preferences (it is easy to get subjective reasons-for-action).

Some religious believers think it is possible to get objective reasons-for-action from God. Specifically, they think that whatever God commands us to do would provide us with an objective reason-for-action. This is the essence of a DCT.

There is one classic objection to DCTs. It can be presented as a terse rhetorical question:

- What if God commanded something terrible?