What do we want from Moral Theory?

Are there real answers to ethical questions? Can we ever truly say that abortion/torture/killing/famine and so forth are wrong? These are meta-ethical questions, i.e. questions about the ontology of moral prescriptions.

Realism is a meta-ethical theory maintaining that there are genuine moral facts; that we can say that abortion/torture/killing and so forth are wrong; and that this is not just a matter of personal opinion.

Realism's problems begin when we look at the demands we place on any moral theory. Smith suggests there are two such demands (or criteria) that a successful moral theory must satisfy.

(a) The "Rightness" Criterion

Suppose you and I are having a robust argument about the propriety of military humanitarian intervention. I argue that whenever there is an active genocide within a country, humanitarian intervention is justifiable. You respond -- in the style of Jeff Lebowski -- "Well, that's just your opinion, man!"

Is your response a conversation-stopper? Is there nothing more I can say on behalf of humanitarian intervention?

For the realist, there must be something more. There must be a right or wrong answer to the question concerning the propriety of humanitarian intervention. The answer can be contextual: it can apply in certain circumstances only. But it cannot simply be an expression of subjective opinion.

(b) The "Motivation" Criterion

As we continue our conversation about humanitarian intervention, I will try to end with a call to action. I will say that we should all participate in, or publicly support and defend the (limited) practice of humanitarian intervention.

But why should anybody change what they do based on my arguments? How could arguments like this possibly change someone's motivational constitution?

For the realist, the recognition of particular statements as being 'moral', automatically provides you with a reason for action, i.e. with motivation.

Now, the anti-realist challenge states that it is actually impossible to satisfy these two criteria at the same time. In other words, that it is impossible for there to be objective moral facts that can tweak subjective motivations. What evidence can the anti-realist marshall in support of this argument?

The Challenge from Humean Psychology

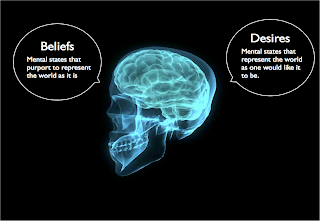

The anti-realist gets his succour from some supposedly basic facts about human psychology. He will argue that there are two types of mental state (or intentional state): (i) beliefs and (ii) desires. Beliefs represent the world as it is; desires represent the world as we would like it to be (see image below).

Since beliefs purport to represent the real world, they are assessable in terms of truth or falsehood. If you claim to believe that there is an invisible dragon in your garage, I can challenge this truthfulness of this belief.

In contrast, since desires only represent the world as we would like it to be, they are not assessable in terms of truth or falsehood. So, if you say "I wish there was a dragon in my garage', I cannot turn around and say "Your desire is false" (I may of course say it is silly, but that is a different matter).

Now the important point is that, according to Hume and the anti-realist, only desires can motivate action. True beliefs may help you to fulfil your desires, but on their own they just don't have the requisite motivational-juice.

This is a problem for the realist because:

- The objectivity criterion demands that moral facts be assessable in terms of truth or falsehood. Thus it would seem that moral facts need to be represented as beliefs.

- The motivational criterion demands that moral facts spur us to action. Thus it would seem that moral facts need to be represented as desires.

It would seem that our psychological makeup cannot satisfy the twin demands of realism.

That's all for now. In the next post, I will outline Smith's attempts to rescue Realism from this dilemma.

No comments:

Post a Comment