(Part one, Part two, Part three, Part four)

This is the last in a series of posts on substance dualism. The series has been following the discussion in William Jaworski's book Philosophy of Mind: a Comprehensive Introduction

1. Inferences to Best Explanation

If substance dualism is true, then we (persons/minds) can exist without bodies. But if we can exist without bodies, then why is it that we all seem to be attached to a body? If the mind-body relation is not a necessary one, then surely some explanation of this correlation is in order? Aristotle posed this very challenge to the dualist back in the day, and it speaks to an interesting line of criticism - one which crops up again and again in the mind-body debate.

The line of criticism in question - in this case directed at the substance dualist - proposes that if a given theory is a poor explanation of the data that needs to be explained, then it can be dismissed in favour of a better explanation.

This brings us to the concept of inference to best explanation (a concept discussed on this blog before) and the correlative concept of inference from a worse explanation. Both work with abductive arguments and, following Peirce's classic schema, look something like this.

- (1) H is some data in want of an explanation.

- (2) E, if true, would account for H.

- (3) E is a better/worse explanation than all other rival explanations (E1....En).

- (4) Therefore, E is probably/probably not true.

Formally, this kind of inference commits the fallacy of affirming the consequent. The comparative exercise undertaken in the third premise, combined with the probabilistic nature of the conclusion, is designed to overcome this problem.

2. Is Substance Dualism a Worse Explanation?

The charge here is that substance dualism, when compared to its rivals, is a worse explanation of the available data, and should therefore be dismissed. How is this charge sustained?

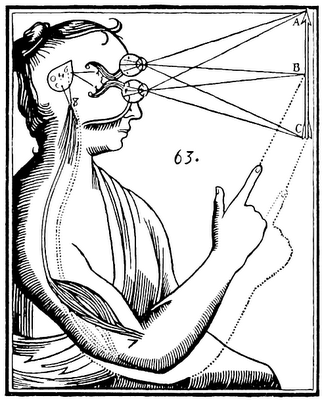

First, consider the data that any theory of mind needs to explain. We've already pointed to one element of that data: the apparently steadfast connection and interaction between minds and physical bodies. But the data is more nuanced than that. For one thing, not just any physical body appears to have a mind: only certain evolutionarily recent organisms have that honour. What's more, mental activity is only correlated with certain parts of those organisms: brains and nervous systems, not hairs and fingernails. How do substance dualists account for these particular correlations?

The answer is that they don't appear to be able to do so. In fact, it is in their interests to show that the connection we observe is apparent rather than real. After all, they want to show that there is no essential connection between mind and body.

This highlights a curious feature of the dialectic between substance dualists and their critics. The critics will want to argue that since other theories of mind do account for the puzzling mind-body correlations outlined above, they are stronger and more rationally compelling. The substance dualists will want to argue that a theory which explains mental-physical correlations has no advantages over its rivals. The correlation can either be dismissed as irrelevant or accepted as a brute fact.

Thus, there appears to be real gap between the two sides over what needs to be explained by an acceptable theory of mind. Alas, gaps of this sort frequently emerge in philosophy.

3. Conclusion

In summary, the problem of explanatory impotence may have some force, but this depends on the data we think warrants explanation. I personally feel that the kinds of mind-body correlations discussed by Jaworski merit explanation. Consequently, I would would be disinclined to accept a theory that dismissed them. To shift from this position, I'd need to be convinced that substance dualism had other epistemic advantages. Since that seems unlikely given the other posts in this series, substance dualism is perhaps best left to one side.

All that said, a recent tactic among some proponents of substance dualism is to point out that even if the arguments in its favour are not all that strong, they are no worse than the arguments put forward in defence of, say, physicalist theories of mind. Thus, to cling to substance dualism is no less rational than to cling to physicalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment