(Part One, Part Two, Part Three)

I've been addressing arguments for and against substance dualism over the past week. In the most recent post on the topic, I considered the first of three arguments against the theory. In this post, I turn to the second of those three argument: the argument from the problem of interaction. In the course of addressing this problem we will encounter some possible refinements of the substance dualist position.

1. The Problem of Interaction

This morning I did something unusual. I decided to write a blogpost on substance dualism: I formulated the intention and then followed through on it by executing the series of bodily movements referred to as 'typing'.

But wait a minute, there's nothing unusual about this is there? Surely we do things like that all the time, i.e. formulate intentions and then carry them out by executing a series of bodily movements? Yes, you're quite right; there's nothing unusual about this in and of itself. But it is quite unusual from the perspective of substance dualism.

The difficulty can be stated in the form of an argument:

- (1) If substance dualism is true, persons cannot causally influence bodies.

- (2) Persons can causally influence bodies.

- (3) Therefore, substance dualism is false.

Once again, it is the first premise that is the main source of controversy here. What can be said in its favour?

2. The Physical Basis of Causation

Quite a lot can be said in favour of premise (1). To see this, we need to bear in mind the ontological commitments of the substance dualist. Remember, they argue that mental entities can exist wholly apart from physical entities; and that physical entities can exist wholly apart from mental entities.

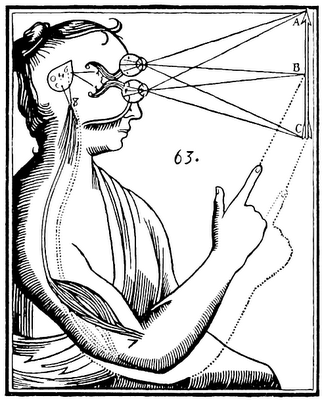

This creates a problem when mental entities are thought to be causing changes in physical entities, as is the case in the intention example given above. You see, everything we know about causation suggests that in order for changes to be caused in a physical object (or for a physical "event" to be brought about) the entity causing those changes must possess two key properties: (i) a spatial location and (ii) the ability to transfer energy. For in the process of physical causation, energy is being transferred from one location to another.

Jaworski uses the example of the combustion engine to illustrate this point. In order for your car to be propelled forward, the following sequence of events must take place: spark plugs in the engine must be ignited by a high-voltage pulse; the ignition of the spark plugs must release energy from the gasoline (petrol) by combustion; the energy from the gasoline must drive the pistons; and they in turn must drive the crankshaft, which drives the axle, which turns the wheels. Each stage in this process involves energy transference from one spatial location to another.

Here then is a serious problem for the substance dualist. Both of the key properties for causation are physical in nature, indeed they are perhaps the very essence of the physical. They are not possessed by mental entities.

So:

- (4) Bodies are physical entities.

- (5) Only entities with a spatial location and the ability to transfer energy can cause changes in physical entities.

- (6) According to substance dualism, persons have neither spatial locations nor the ability to transfer energy.

- (1) Therefore, if substance dualism is true, persons cannot causally influence bodies.

3. Substance Dualist Responses

With premise (1) now fully defended, the problem of interaction seems to be robust. How can the substance dualist respond? There are several possibilities, some of which lead us towards more refined versions of substance dualism.

Let's consider the less-refined rebuttals first. One is to simply reject premise (1) (or, more precisely, premise 5) and argue that non-physical causation is intelligible, or at least no less intelligible than purely physical causation. The idea here is that the ability of physical entities to cause changes in one another is basically an inexplicable brute fact. We simply have to accept it as a given. So why not accept the ability of mental entities to cause changes in physical entities as a similarly brutish fact?

One problem with this line of response comes from the law of conservation of energy. It is a basic principle of physics that the amount of energy in a closed system is fixed: add up the total energy before and after an event in such a system and you will get the same figure; energy is simply moved around from one location to another. If mental entities were causing physical events then we would expect energy to be added to the relevant system (in this case the human body and its surrounding environment) from outside. This would require a violation of the conservation law that does not appear to take place.

We can map this exchange out as follows:

- (7) If physical-physical causation is accepted as a brute fact, so too can mental-physical causation be accepted as a brute fact.

- (8) Mental-physical causation would involve the violation of the conservation law of energy, this law does not appear to be violated.

This argument effectively presents the substance dualist with a dilemma: they can either have mental-physical causation or the laws of physics, they cannot, or so it seems, have both.

It should be noted in passing that in addition to being part of an argument against substance dualism, the conservation law of energy is often used to support mind-body physicalism.

4. Parallelism and Occasionalism

If rejecting premise (1) seems too much to bear, the substance dualist can always reject premise (2). This would mean a rejection of the apparent causal relationship between mental entities such as intentions and physical acts such as bodily movements. Such a rejection would leave us with the unexplained fact that mental entities seem to be very closely correlated with certain physical acts. How, we must ask the dualist, can this be the case?

In answering this question, the substance dualist will be forced to introduce one of two possible refinements to their original position. The first possible refinement is called "parallelism"; the second is called "occasionalism".

Parallelists believe that mental and physical systems, although ontologically distinct, run in parallel to one another. This creates the impression that events in one system are causing changes in the other system, but this is purely coincidental.

An analogy with clocks is often used to illustrate the point. Suppose you have two clocks, A and B. Both are wound up at the same time (remember when you had to wind-up clocks?) and thus run in synchrony. Now suppose you remove the chimes from clock A and the hands from clock B. As a result, clock B will appear to chime when clock A's hands arrive at a particular time. This might create the impression of a causal link between the two clocks but that is all it is: an impression. There is no real causal link. Something analogous could be taking place between the mind and the body.

Parallelism is certainly a possibility, but how plausible a possibility is another question. In the clock analogy we have an explanation for the parallelism; in the mind-body example we have no such explanation. Thus, accepting parallelism would seem to require accepting a significant, inexplicable coincidence. Sort of like the coincidental relation between epistemic faculties and moral truths proposed by some moral realists. This seems like a big pill to swallow just to save the substance dualist worldview.

- (9) The mental and physical system may simply be running in parallel, thus creating the impression of a causal link between them.

- (10) Accepting parallelism would force us to accept a significant coincidence as a brute fact, we should be reluctant to do so unless there are other compensating benefits.

An alternative way in which the substance dualist can reject premise (2) is by adopting an occasionalist view of mind-body causation. According to this view, God acts as a causal middleman producing changes in the physical body that correspond to changes in the mind.

Leaving aside any challenge to the explicitly theistic grounding for this view, there are two objections that need to be considered. First, it has the strange consequence that God is the only real agent in existence, i.e. the only one that can bring about changes in the real world that deserve to be called "actions". This has a further consequence. Agency is an essential precondition for moral responsibility. So if none of us are really agents, then none of us are ever morally responsible. That will strike many as absurd.

Finally, the theory has the unenviable whiff of ad-hocery about it. In other words, the supposition that God acts as a causal middleman is being adopted purely to save face. It is generally agreed that the acceptance of ad hoc principles of this sort is to be avoided.

- (11) God could act as a causal middleman between persons and bodies.

- (12) The assumption that God acts as causal middleman: (i) leads to the absurd conclusion that God is the only agent; and (ii) is ad-hoc.

5. Conclusion

In the end, it seems like the problem of interaction forces the substance dualist into an uncomfortable corner. They can manoeuvre their way out it, but only by accepting some epistemically costly doctrines. They need to ask themselves whether the commitment to substance dualism is really worth these costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment