[Note: I’m hoping that this might end up being part of longer a series, but I don’t want to get too ambitious at this stage. I would appreciate any comments and suggestions on improving my analysis, but do bear in mind that I have two more entries on the objectivity issue planned]

“So many debates in philosophy revolve around the issue of objectivity versus subjectivity that one may be forgiven for assuming that someone somewhere understands this distinction.”

(Richard Joyce, “Moral Anti-realism”, SEP)

I like Richard Joyce. He has written some lucid and highly engaging stuff on moral philosophy over the years. Now I don’t ultimately agree with him, but I like the above quote because it captures one of the key difficulties in all philosophical arguments: the imprecision of terminology.

Many concepts that we use in everyday speech, like “objectivity” or “subjectivity”, have been subjected to highly intricate and elaborate philosophical theorisations. So to say that something is objective, or to affirm the existence of objective entities, can be both uninformative and misleading.

I mention all this because, of course, the centrepiece of Craig’s moral argument is the claim that “objective moral values and duties exist”, and that they can only do so if God exists as well. What does Craig mean by this? In the text of Reasonable Faith (p. 173, to be precise), Craig dedicates two paragraphs to directly answering this question (further indications of what he means by “objective” are peppered throughout his discussion). Let’s see if things become clearer if we subject these paragraphs to close scrutiny.

1. Paragraph One: Objectivity and Relativity

For ease of reference, I’ll quote the first paragraph in its entirety here (emphasis added):

“Let me say something to clarify the distinction between something’s being objective and something’s being subjective. To say that something is objective is to say that it is independent of what people think or perceive. By contrast, to say that something is subjective is just to say that it is not objective; that is to say, it is dependent on what human persons think or perceive. So, for example, the distinction between being on Mars and not being on Mars is an objective distinction; a particular rock’s being on Mars is in no way dependent on our beliefs. By contrast the distinction between “here” and “there” is not objective: whether a particular event, at a certain spatial location occurs here or there depends upon a person’s point of view.”Noting the highlighted phrases, it becomes pretty clear that I think Craig makes two interesting clarifications here about the nature of objectivity. I want to discuss these in some detail.

The first clarification is the idea that in order for something to be objective, it must be mind-independent. In other words, like the proverbial tree falling in the forest, an objective entity continues to exist even in the absence of a mind which perceives its existence.

I like to think of this as the core, or privileged, sense of “objectivity”. In other words, as the sense that is closest to that implied in the paradigmatic applications of the term. But because I think objectivity is a confusing term, I will use the more precise term “mind-independence” to refer to this sense of objectivity. Similarly, I’ll use the term “mind-dependent” to refer to that which is typically considered under the term “subjective”.

The second interesting clarification comes from Craig’s use of the indexical terms “here” and “there”. When I see this it immediately sets certain alarm bells off in my head. Indexicals are probably the distinguishing mark of relativistic claims (moral or otherwise). So I take it that Craig’s use of the terms here is intended to exclude the relative from the domain of the objective.

But this raises the question: what does it mean for something to be relative? Roughly, a proposition or state of affairs is relative when its truth/falsity (or existence/non-existence) cannot be determined on its own terms, but only relative to some other proposition or phenomenon.

To modify Craig’s example, the claim “there is a desk ten feet in front of me” can only be assessed for its truth value relative to my current spatial location. It cannot be assessed in the absolute. It is perfectly possible for this claim to be true for me and not for you; no contradiction is entailed by this possibility (but note: it can still be true or false).

2. Do we need to distinguish the objective from the relative?

If Craig is conflating relativism and mind-independence in the course of clarifying the nature of the “objective” in paragraph one, then there might be a problem. While it might generally be true that mind-dependency and relativity are present at the same time, it is not necessarily true.

Richard Joyce actually makes this point in the course of his article on Moral Anti-realism. He argues that there can be mind-independent relativisms and mind-dependent absolutisms. As follows:

Mind-Independent Relativism: Michael Jordan might be tall relative to most other men, but he might be average in height relative to other basketball players. Thus the truth of any claim about his tallness is going to be relatively determined, but at the same time there is nothing particularly mind-dependent about it.

Mind-Dependent Absolutivity: We might decide that “X is good” means “My grandmother approves of X”. This would make goodness a mind-dependent property, but would it make the claim “X is good” a relativistic one? No; the truth conditions of that statement would hold true for all individuals at all spatial and temporal locations (it might be epistemically difficult for some of those individuals to gain access to those truth conditions, but that’s another matter).

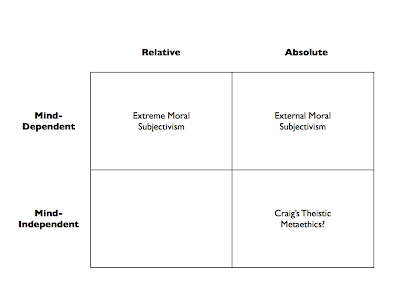

This suggests that we can construct the following two-by-two matrix.

In future entries, I’m going to suggest that this two-by-two matrix is inadequate because there are even more dimensions to be considered when assessing metaethical theories. But for the time being we can use it to perform two interesting exercises.

First, considering the two dimensions we have identified, ask yourself: what is it that we would like from a metaethical theory? Is mind-independency really that important? Or is absolutivity the most important thing? I’m not going to propose any answers here. But it’s worth thinking about since one of the most common ways to do metaethics is to first specify what we demand from our moral terms and then look around to see if any of the available theories satisfy these demands. It could well be that no single theory satisfies all the demands and so when it comes to actually figuring out which theory is the most acceptable we have to compromise.

The second exercise we can perform is to try to position some moral theories on the grid. I have provided an illustration below. I put “extreme moral subjectivism” in the top left. This is the theory that makes moral truth entirely dependent on your subjective whims, which can vary from time to time and place to place. I put “external moral subjectivism” in the top right. This is theory that makes moral truth dependent on the subjective whims of another. This would be akin to the grandmother subjectivism discussed above. I put nothing in the bottom left because I am unsure what belongs there. And I tentatively place Craig’s preferred metaethics in the bottom right.

The placement is tentative for a couple of reasons. Although it is true that -- based on what he has said in paragraph one -- Craig wants his theistic metaethics to belong in the bottom right quadrant, his desires are obviously not going to determine the issue. We need to see whether his actual theory merits this placement. It may not.

For instance, Luke Muehlhauser has been arguing for some time that Craig’s theory really belongs in the upper right quadrant since he makes moral truth dependent on God’s mind (much like I did with my grandmother earlier in this post).

We need to be somewhat careful about this claim since it raises issues relating to the Euthyphro dilemma and Craig has some responses to this (or, rather, he adopts the responses of others) which I’ll have to comment on later (even though I have discussed them before).

But I should note that I have similar concerns with Craig’s theory myself. Elsewhere in his discussion, Craig seems to endorse the idea that moral obligations are relativistic. To be precise, he endorses the claim that moral obligations arise from relations between human beings and God. This would seem to make obligations (if not values) relativistic. Now maybe he could argue in response that the obligations we have towards God never change and are hence (contingently) absolute. The problem with this is that it is not obviously or necessarily true. For instance, I am sure a Christian (who believes in Hell) would have to believe that our obligations changed in the post-Jesus era. If this is right, then our obligations are not absolute.

Anyway, that’s enough for this post. I’ll look into paragraph two next time round.

No comments:

Post a Comment